Blog

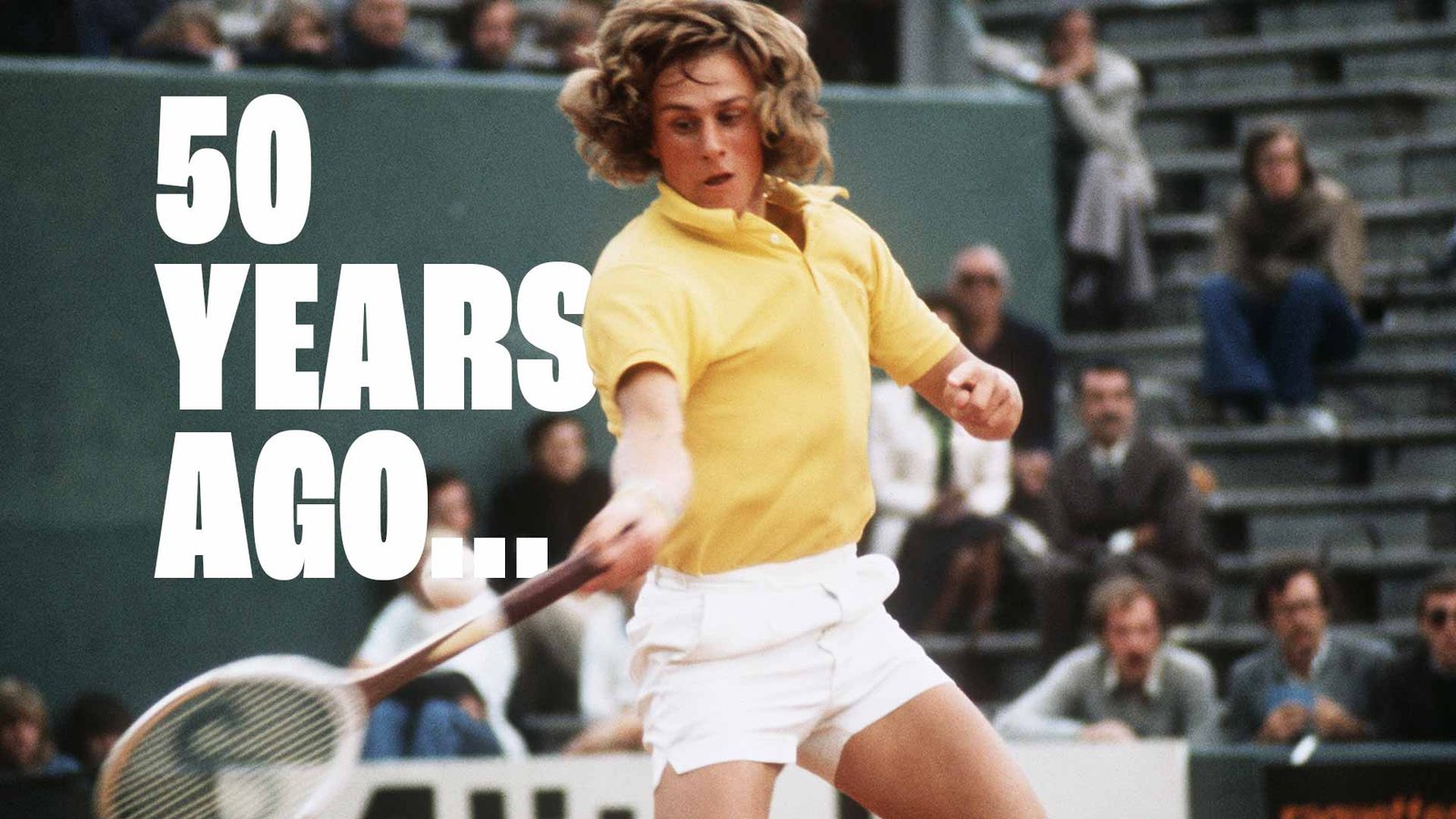

1974: The year Bjorn Borg The Roland Garros Championship, Fifty Years Later

His court speed and ability to play huge points so well were on another level, and his first-serve % under pressure was outstanding. His groundstrokes were startling in their depth, and his court speed was on another level. When Open Tennis was still in its infancy, those who competed on the international circuit were aware that Bjorn Borg was on his way. When the precocious 15-year-old, who had just graduated from high school, showed a new level of physique, intelligence, and consistency, many people predicted that the classic serve-volley tennis would be challenged and eventually ended.

His court speed and ability to play huge points so well were on another level, and his first-serve % under pressure was outstanding. His groundstrokes were startling in their depth, and his court speed was on another level. When Open Tennis was still in its infancy, those who competed on the international circuit were aware that Bjorn Borg was on his way. When the precocious 15-year-old, who had just graduated from high school, showed a new level of physique, intelligence, and consistency, many people predicted that the classic serve-volley tennis would be challenged and eventually ended.

There had been baseliners in the past, but the Swede was able to show resilience time and time again by concentrating entirely on the next shot of the match. Instead of giving in to critics of his technique, he was able to absorb punishment in matches and demonstrate tenacity. For that was the only thing that Borg had ever known since he hit a ball against the wall of his garage on Torekallgatan 30 in Sodertalje for the first time. During the first three years of his career, he did not be given any coaching. “When I left school, I gave myself two or three years before I could possibly return to my studies,” recalls Borg, who is now fifty years old during this time period. He never had to turn around and look back.

Borg told ATPTour.com from his home in Stockholm, “I took training just as seriously as matches from a young age, and that was one of the keys to my breakthrough and career.” Borg was speaking from his time as a professional tennis player. One of my greatest talents was my mentality, and I walked onto the court to train myself to concentrate on what I was doing.

Initially, I was able to concentrate for one hour, and then for two hours. When I was first starting out on the professional tour, I was certain that I could continue for the whole of the match. When I was in training, I would clear my mind and focus solely on the here and now, thinking about the next ball and the next shot. Switching on and off, as well as winning the next point, would be my primary emphasis. “I have to come out on top. This is the impossible ball that I need to get back.'”

When Percy Rosberg first encountered Borg, who was 11 years old at the time, in 1967, he immediately recognized a remarkable gift that he possessed. Even in modern times, the 91-year-old continues to trek the three minutes from his flat to SALK Hall, which he considers to be his second home.

“Bjorn jumped into a group of ten talented children,” said Rosberg, who had formerly been the Swedish No. 4 behind talented athletes such as Sven Davidson, Uffe Schmidt, and Jan-Erik Lundqvist. “A boy got sick, so Bjorn jumped into a group of ten talented children.” “Bjorn moved me around the court for twenty minutes during our first hit, getting every ball back and moving me from corner to corner. He did this for the entire hour.” His footwork was just fantastic. In an effort to put him in his place and improve his backhand technique, I attempted to do so, but it was unsuccessful. The length of the shot was completely under his control. Even at that moment, I had the impression that Bjorn was already aware of the fact that he would emerge victorious if he was able to score one more goal than his rival. Although it is possible for anyone to have strong strokes, a player who has a good head will perform well when they are under pressure. Prior to the beginning of the 1974 French Open at Roland Garros, Borg had already accomplished a great deal in his career with his successes. The former third-ranked player in the world, Tom Okker, who currently resides in South Africa for six months of the year, recalls that “we all saw his potential.” Even back then, his approach to the game remained the same: he focused on maintaining his fitness, strength, and quickness around the court.

As Borg flew down from Stockholm to Paris after practice, only a matter of hours before his first-round match against France’s Jean-Francois Caujolle, at four o’clock on Monday, his mentality and approach to fitness training were already set in stone. In a legal sense, Borg was a boy when he became the youngest Italian Open champion in late May 1974. However, Borg’s mentality and approach to fitness training were already set in stone. Rosberg, who had developed Borg’s trademark topspin groundstrokes, and Lennart Bergelin, who had been like a “second father” to Borg, had made sure that this was the case. “We took one match at a time,” Borg adds in reference to Bergelin and their ability to concentrate. “Now it’s the next guy,” the coach said. “You’re playing this match.” We did not look in the future. He could tell by looking at my face whether or not I was prepared, therefore he was aware that I was in good form. First, he would tell me who I would be playing, and then we would get ready.

The recollection of Borg’s second visit at Roland Garros, which came after he was eliminated in the fourth round in 1973, continues to bring a smile to Rosberg’s face even after fifty years have passed. During the Friday and Saturday, Bjorn and I worked out together. After that, I told him, “Now, you should get ready to go to Paris, and you’ll play your first match on Monday afternoon.” “No,” Bjorn responded. On the following Sunday, I would like to work out with you here. I am unable to practice with anyone at the moment. Sunday is the day that I work out with you. In order to prepare for his first match in Paris, we worked out together in Stockholm the day before. It was a complete and utter idiot! Are there any players in today’s game that would show up just a few hours before their first match?

Borg was able to take the game that he had initially demonstrated to Rosberg all the way to the top. Despite the fact that Borg, who was only 11 years old at the time, had a two-handed backhand, Rosberg believes that he focused more on hitting his forehand than his backhand. Because he did not shift as well to his backhand side, I could understand why he would take that position. When he came to me, I guided him through the process of learning how to dance and how to step for his backhand positions. He was the most diligent and passionate learner I had encountered. During his first Davis Cup match for Sweden, when he was only 15 years old, he utilized the same strategies: he would retrieve the ball back, his opponent would hit one more ball, and he would use his footwork to his superior advantage.

After having breakfast at Arlanda Airport in Stockholm, Borg, Bergelin, and Rosberg arrived in Paris and immediately proceeded to Roland Garros, which is located in the south-west corner of the city from the airport. That very first evening, Borg came back from a deficit of 1-4 in the deciding set against Caujolle, coming within two points of an early exit. Over the course of the subsequent twelve days, the third seed was able to negotiate victories over players such as the American Erik Van Dillen, the ninth seed Raul Ramirez of Mexico, and Harold Solomon, another American. The statement made by Borg was, “I didn’t mind playing five-setters.” Even before I won my first Grand Slam tournament, I had the impression that my mental strength was quite high. It never bothered me to play five sets. I never felt fatigued when playing tennis; both my body and my mind were in a state of freshness from the game. I had the advantage of being young, and I was able to win those crucial points.

By the 16th of June, when Borg’s wooden racquet arrived on the Parisian landscape, everything had changed. A swarm of autograph hunters and photographers had gathered on the court to capture the moment. Borg was a major champion before he wore his headband, grew a wispy beard, had an aircraft fly forty newly strung racquets (35 kilograms or 77 pounds) from his favorite stringer in Stockholm to all over the world, wore clothing that was tailored to his body, and observed a multitude of daily routines that all became a part of his iconic spirituality. I am 18 years old and 10 days old. It was when he returned to a tournament in an effort to keep his title that he began to believe in superstitions, such as “rushing out to my preferred chair on the court.”

After defeating Manuel Orantes, a Spaniard who is widely considered to be the best clay-court player in the world, with scores of 2-6, 6-7(4), 6-0, 6-1, and 6-1, Borg experienced a sense of personal amazement as he sat down in his courtside chair. Orantes, who is now fifty years old, says, “I arrived with a lot of confidence, but Borg was a phenomenon and had progressed very quickly.” While Borg was scanning the throng of 18,000 people, he kept a sheepish smile on his face. He was looking for Bergelin, who had been without Rosberg’s coaching help since the quarterfinals. As the match was being played, there was a consensus that Borg was destined to be “a player for the future.” The memory of Stan Smith is that “not today…”

According to Borg, “I had the feeling that I was going to be the favorite going into the final.” Although I believed I had a strong chance of winning, the fact that I was able to compete in the final of a Grand Slam tournament was a significant accomplishment for me. It also belonged to Orantes. It was because of his age that he was under additional strain. I was still certain that I had a strong chance of winning, despite the fact that I had lost the first two sets. I was still under the impression that I had a chance after the tie-break.

pertaining to matches”

-

Blog7 months ago

Blog7 months agoThe next spy thriller starring Rami Malek has created a movie that is a competitor to Slow Horses Season 5.

-

Blog1 month ago

Blog1 month agoTrener Pogoni Szczecin Wskazuje Pięciu Kluczowych Zawodników na Letnie Okienko Transferowe

-

Blog9 months ago

Blog9 months agoGabriela Sabatini, la mejor tenista argentina de la historia, visible y Orgullosa

-

Blog4 weeks ago

Blog4 weeks agoPrezes Widzewa Łódź Michał Rydz wskazuje swoich kandydatów do składu na przyszły sezon

-

Blog9 months ago

Blog9 months agoThere are seven quotes from Gabriela Sabatini that explain why she was so far away from the sport of tennis, her rivalries with Graf, and the players who are most admired by her at the present time.

-

Liverpool1 year ago

Liverpool1 year agoFull Reason why 56-year-old Liverpool manager Jurgen Klopp angrily storms out of interview after Manchester United win vs Liverpool FA Cup quarter final

-

Manchester United1 year ago

Manchester United1 year agoMain reason Amad was sent off during Manchester United vs Liverpool FA Cup quarter-final match

-

Blog1 month ago

Blog1 month agoWidzew Łódź przygotowuje się do letniego okna transferowego i wystawia zawodników na sprzedaż